Cognitive Accessibility Challenges in The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom: An Autoethnography from the Perspective of an Autistic Researcher

Cognitive Accessibility Challenges in The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom

“I have no idea what to do.” I squeezed my eyes shut, burying my face in my hands, “I can’t think.” My brain felt hot as I kept fumbling with the game controls; there was too much to learn too fast. I finally gave up and handed the Switch controller to my partner. “I’m gonna go outside for a few minutes,” I said. “I need a break.”

My partner paused the livestream and followed me to the patio. “Hey,” they said. I turned and slumped my head into their chest. They hugged me, putting their chin on top of my head, “We don’t have to keep playing if this is too much for you. We can stop whenever.”

I pulled away, still defeated. “No. I want to keep playing. I mean, it’s fun, I guess. It’s just these puzzles – I don’t see those kinds of things. This is a game made for boys to build, like cars and stuff.” I gestured to the living room, “This isn’t a Zelda game. This is a game for gamers. I just feel like they left the lifelong Zelda fans behind with this one.”

This experience serves as the impetus and the material for my autoethnography. In May 2023, my spouse and I decided to do a weekend-long livestream of the newest release in the Legend of Zelda series: Tears of the Kingdom. I have been a loyal Zelda fan since the 1998 release of Ocarina of Time on the Nintendo 64 (IGN, 2023). So after 25 years of patronage, I felt bitter and abandoned after getting my hopes up in the months leading up to Tears of the Kingdom’s release.

Feeling left behind has been a common thread throughout my life. Growing up, I often felt alienated from those around me for reasons I could never quite explain. I remember grade school teachers calling me eccentric as a thinly veiled insult for not fitting in with my peers. Outside school, I was carted to different therapists and psychiatrists by my concerned parents only to be misdiagnosed more than once with different mental health disorders. As a mixed race black girl in the late 1990s, Autism was not yet a viable diagnosis for anyone but young, white boys (Diemer et al., 2022). It wasn’t until I turned 30 that I learned I had Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), a highly individualized developmental disability often characterized by social communication problems, difficulties in sensory processing, delayed speech and cognitive skills, and repetitive behaviors and/or movements (CDC, 2022).

Learning I was autistic didn’t change anything about my life outside of adding a label to my identity, but it did serve to add another layer to my existing worldview. Like many other individuals with ASD, I have always felt as if I missed the handout for the “Basic Human Interaction Rules” manual. Along with a constant out-of-place feeling, I also learn and process information a bit differently than people without ASD (Haigh et al., 2018). While there are no intrinsic morals tied to any of these statements, many are still working towards ASD acceptance and accessibility in many facets of life.

One of these facets is video game accessibility. Although design principles established by the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) and Game Accessibility Guidelines (GAG) provide a set of standards and recommendations to make web content more accessible, these lists are not all-inclusive requirements for video games (Cairns et al., 2021). Further, noting what happens when video games do not abide by these standards can shed light on the importance of implementing these inclusivity factors. According to Self-Determination Theory, there are three basic human psychological needs for individual health and well-being: autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Without meeting these needs, negative outcomes such as frustration and emotional exhaustion can result (Van Assche et al., 2018). Despite having sets of standards for accessibility, many video games still fall short, leaving players with cognitive disabilities feeling disregarded.

These issues are what brings me to this autoethnography. Feeling these negative emotions after playing the first 20 hours of The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom (TOTK) prompted me to revisit the livestream files and address the cognitive accessibility issues from the perspective of not only a researcher, but also a person with ASD.

Literature Review

In the existing literature, ASD research tends to suffer from what Srinivasan (2023) calls a “narrow research bias” (para. 10) with needlessly exclusionary criteria that usually focuses on young men and boys (Sohn, 2019). Because of this, ASD research often severely underrepresents female and black populations, and autistic black girls face near complete neglect from scientific research due to their multiple marginalized identities (Diemer et al., 2022).

When it comes to video game accessibility research, there are also unexplored areas of study. Literature tends to focus mainly on higher needs children with ASD and the design of therapeutic and educational games rather than serious (i.e. just for fun) games (Salvador-Ullauri et al., 2023; Spiel & Gerling, 2021; Valencia et al., 2021). Even so, scholars agree that video games can provide a safe space for individuals with ASD to practice social interaction and focus skills, lessen symptoms of social anxiety, and improve overall perception and cognition (Cairns et al., 2021; Kourtesis et al., 2023; Salvador-Ullauri et al., 2023). However, adults with ASD still face accessibility issues when it comes to gameplay features, user interface (UI) design, reading comprehension, and sensory overload problems (Bozgeyikli, 2018; Cairns et al., 2019; Mazurek et al., 2015; Pavlov, 2014). In addition, Valencia et al. (2021) highlight the fact that many studies have assessed the usability and user experience (UX) of systems designed for individuals with ASD using evaluation methods primarily focused on users without disabilities. These authors agree that while video games can be a source of therapeutic enjoyment, there is a lack of research evaluating the unique needs of individuals with ASD from their perspective.

It is also worth noting that accessibility issues do not start and end with the user. The lack of accessible video game design can also stem from poor synergy between mental health professionals, user preferences, and game designers' knowledge (Malinverni et al., 2017, p 538). Integrating interdisciplinary knowledge from different perspectives as well as accounting for player preferences throughout the development process is vital to creating an effective and enjoyable game (Malinverni et al., 2017; Mazurek et al., 2015; Pavlov, 2014). This finding highlights the need for both clinical and user-centered research.

One study conducted by Mazurek and colleagues (2015) prioritizes user-centered research and investigates the motivations for play among participants with ASD, identifying their likes and dislikes in serious video games. Participants cited entertainment, stress relief, and immersion as top motivations for autistic players (p. 125). However, negative physical responses such as headaches due to overstimulation were cited as gameplay deterrents (Mazurek et al., 2015, p. 126). Overstimulation or sensory distress can also stem from misreading or failure to understand nonverbal cues used to drive the overall flow of the video game (Costello & Donovan, 2019). These difficulties may affect immersion, or ‘presence’ factors in gameplay, a concept explored in an article by Slater (2009).

In an attempt to combat these issues, scholars have developed guidelines and assistance tools for designers (Cairns et al., 2019; Pavlov 2014). Additionally, design principles as established by organizations like the WCAG and GAG provide an international set of standards and recommendations to make web content more accessible. However, even with these tools and guidelines, Cairns (2019) states that “while a checklist can give reassurance that a game is in some ways accessible, it can give very little help when a game fails to meet the guidelines” (p. 67). This statement also harkens back to the importance of synergy between designers, clinicians, and users during the development process.

As a late-in-life diagnosed black autistic female who frequently plays video games, I am intimately familiar with the frustrations and difficulties in gameplay much like the issues listed above. Cairns et al. (2021) note that “the value of accessible games is not just mere play but playing the same games as everyone else” (p. 262). Essentially, the goal of accessibility should be to even the playing field so that everyone, regardless of ability level, can enjoy video games equally. With this goal in mind, I consider the following research questions to guide my autoethnography:

RQ 1: What unique challenges do adults with ASD face when playing serious video games?

RQ 2: What are the negative emotional consequences that stem from lack of accessibility features?

RQ 3: What are some proposed game design modifications that can be made for adult autistic populations?

Method

This research aims to examine how ASD-related cognitive challenges affect gameplay in terms of competency and enjoyment. To that end, my research will also shed light on how the lack of accessibility features in TOTK negatively affected my mental and emotional state. To do this, I engage in autoethnography to discuss and analyze my lived experience playing this new game with my partner during the game’s launch weekend.

Autoethnography is a relatively new data collection method that emerged out of critiques of ethnography (Adams et al., 2017). It focuses on personal experiences and storytelling to provide individualistic cultural accounts that may oppose and unmask dominant and harmful ideologies (Adams et al., 2017). This approach also aims to systematically analyze personal experiences to gain insights into cultural phenomena (Ellis et al., 2011). Although autoethnography has been criticized due to its perceived lack of rigor and self-serving purposes, this method can be used to link theories and concepts from the literature to personal experiences and provide much-needed insight into broader cultural phenomena (Jones, 2016).

Engaging in this method allows me to connect and integrate my personal experience as an individual with ASD into the larger narrative of video game accessibility. Also, as a part of an underrepresented cultural group, this autoethnography may provide a counter-narrative to the existing research on individuals with ASD (Adams et al., 2017). In identifying these problems, developers and researchers will be able to make more informed decisions when determining and reducing barriers to gameplay.

In essence, this autoethnography will act as a post-launch accessibility test for overlooked cognitive challenges. I hope that my experiences can contribute to fostering greater empathy and a deeper understanding of the challenges faced by individuals with cognitive disabilities, such as ASD, when encountering inaccessible video games.

Launch Weekend

Before (TOTK) came out on May 12th, 2023, my partner and I planned to do a weekend-long release stream on the popular livestreaming service, Twitch. We streamed in six- to seven-hour chunks from Friday afternoon, May 12th, 2023 to Sunday, May 14th, 2023 on my partner's Twitch channel. During gameplay, I became increasingly frustrated at my apparent lack of understanding and competency of the new game controls. I had grown accustomed to the game mechanics and controls of TOTK’s predecessor Breath of the Wild which came out in 2017. It seemed as if Nintendo was heading into uncharted territory with TOTK, and I was having significant difficulties adjusting to a new method of gameplay. I found myself masking, (using strategies, whether consciously or subconsciously, to hide autistic traits from others in order to appear more ‘normal’) (Cook et al., 2021) attempting to seem unfazed by my frustrations. These masking attempts were mostly unsuccessful as I frequently verbalized my grievances on stream. I also tend to be a highly expressive person and usually incapable of hiding my emotions. However, the weekend-long launch stream was, overall, a success and I still consider myself a Legend of Zelda fan despite my challenges.

Data Collection

To gather data, I first scrubbed through the nearly 20 hours of stream footage, noting where I was playing (i.e. holding the controller), and where my partner was playing. To note, our Twitch livestream showcased the video gameplay as well as a small viewing panel of me and my partner. I collected about twelve hours of reviewable data and carefully watched the footage back. While watching the footage, I kept a digital (Microsoft Word) journal, reflecting on memories of my physical and emotional state as well as noting facial expressions of confusion, distress, frustration, and other similar emotions on the livestream. I also took transcripts of discussions mentioning gameplay difficulties, whether with my partner, alone or with chat participants. Although I received my partner’s consent to use our conversations and footage, in the video examples that follow, I have used censor bars to protect their identity.

Reflexivity Statement

While touching on ethical concerns, it is crucial to note the importance of reflexivity when engaging in autoethnography (Wall, 2006). In identifying the difficulties I had, it is important to differentiate between ASD-related problems and general, more personal issues of learning a brand-new game while streaming to a public audience. I would also like to point out that I have what some may call ‘high-functioning’ or Level 1 autism (Roberts, 2022), and currently require minimal external support. I am a graduate student, I can communicate my thoughts and feelings verbally and nonverbally most of the time, and I am able to live on my own. Though I might not be the best at reading social cues or participating in conversation, I am still perceived as able-bodied. And in many ways, I am. However, many autistic individuals do not share my experience and require much more support. My hope is that, as a researcher and a person with ASD, I can contribute a unique voice to the existing literature.

Analysis

As an autistic person, throughout my life I’ve been made to feel less intelligent than my peers, excluded, incompetent, and overly sensitive. While none of those things are necessarily true, playing Tears of the Kingdom resurfaced all of those insecurities. The game controls were more complicated and overwhelming than its predecessor, Breath of the Wild, and the new puzzle mechanics seemed like they were made for a different brain than mine. It didn’t feel like the cozy, welcoming Zelda experience to which I’d grown accustomed.

In analyzing the data, I approached my transcripts, notes, and footage similarly to heuristic inquiry as noted by Wall (2006). She suggests autoethnographers approach data analysis by engaging in “thorough discussion, introspection, and thought (immersion and incubation) until themes and meanings emerge” (Wall, 2006, p. 5). In other words, much like traditional data analysis, autoethnography requires researchers to be highly reflective when partaking in the cyclical nature of coding. This method involved many conversations with my partner, poring over the data, writing more notes, and revisiting codes and themes multiple times.

Ultimately, after reviewing the video footage and transcripts, I employed thematic analysis and found several challenges directly related to ASD and identified key recommendations and modifications to improve overall cognitive accessibility. This involved using open coding of video footage, transcripts, and a data collection journal I kept that detailed my emotional state during key gameplay moments. The initial codes were then categorized further and distilled into axial codes and finally, using selective coding (Corbin & Straus, 1990; Memzir, E. A. 2020), into core themes. The following paragraphs will detail my findings through reflection and video examples as well as provide accessibility recommendations for future games.

Findings and Discussion

From my analysis, two core themes surfaced: Cognitive Processing Impairments and Narrative Regulation. These themes encapsulate the overarching challenges related to ASD that I faced during gameplay. Before diving into a detailed exploration of my findings and offering suggestions for future game development, I will provide brief definitions for each theme.

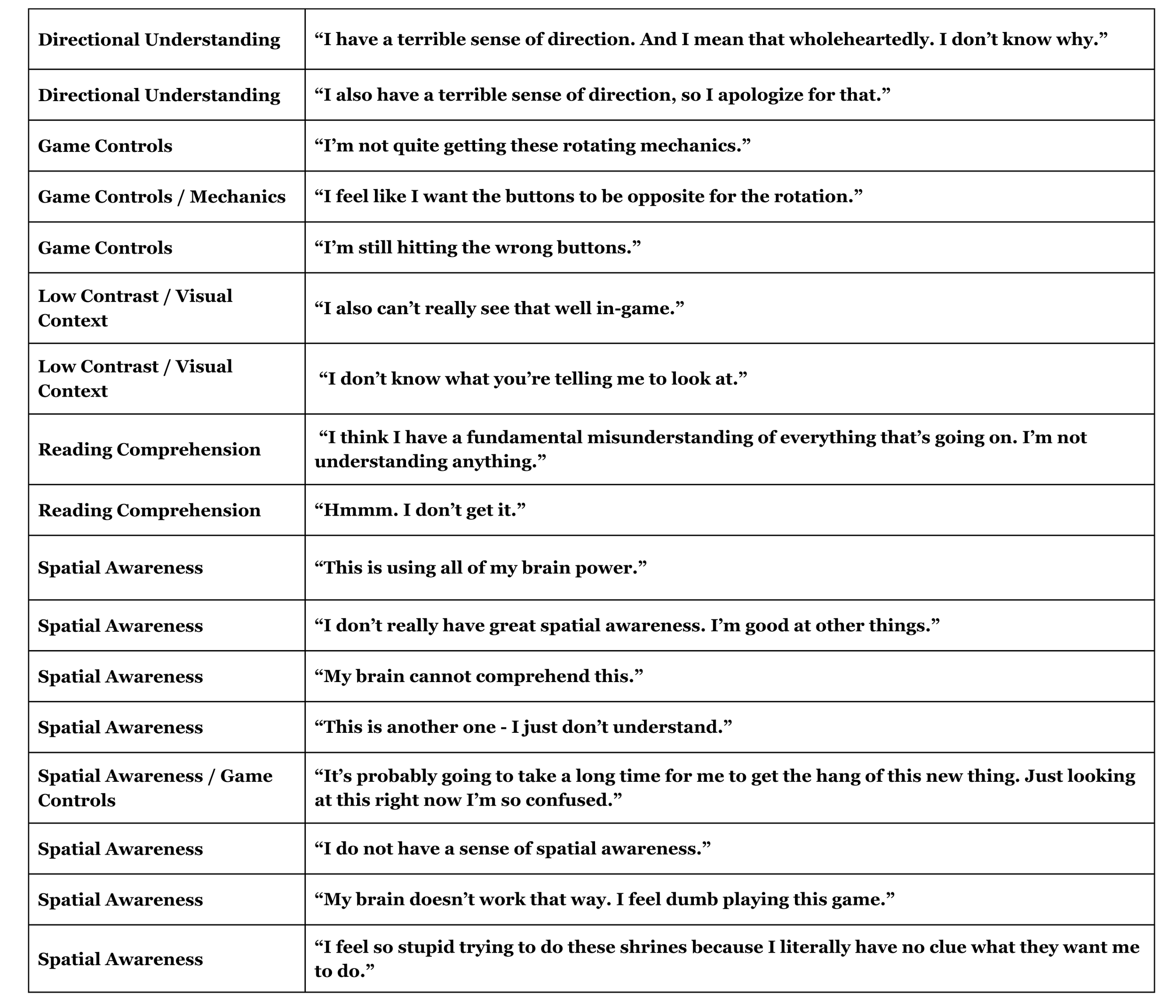

Table 1

Cognitive Processing Impairments

Cognitive Processing Impairments deals with difficulties and delays in understanding new and important information. In my analysis, data suggest that the two factors leading to these Cognitive Processing Impairments were delayed processing and visual data processing.

Delayed Processing

Delayed processing is a cognitive impairment commonly reported in individuals with ASD (Beker et al., 2018). This impairment means that it takes longer to absorb, make sense of, and respond to incoming information (Haigh et al., 2018). In a gaming context, I found that my delayed processing was the result of a high difficulty level and issues with grasping game controls/mechanics. These factors meant that there was more information at a baseline to take in and process. This, in turn, led to delays in game competency and overall enjoyment lasting well beyond the tutorial level. These results are consistent with Mazurek et al’s (2015) study which noted that unrealistic difficulty levels and certain game mechanics are common gameplay deterrents for autistic individuals.

In emotionally handling these impairments, I felt the need to constantly announce my incompetencies as if verbalizing my struggles would somehow validate or soften them (Table 1). That being said, I didn’t want to be a whiny, wet blanket on Twitch. My friends were watching, my partner’s friends were watching, and I didn’t want to be responsible for bringing down what was supposed to be a fun weekend. But keeping up a cool front became more difficult the more incompetent I felt. By the end of the weekend-long stream, I felt battered and mentally exhausted. In the video example below, I am having trouble grasping the rotation mechanics and controls to build a car. I am getting increasingly frustrated with my lack of competency in understanding the controls, and in turn, it is affecting my overall comfort with the game.

As noted by the WCAG (2023) and GAG (2020), one element that may have made learning the game controls easier is adjustable key bindings, or changing which buttons control a specific action. Shortly before this clip, I mentioned that I wanted opposite buttons for the rotation mechanics. I kept making the same button-pressing mistakes and felt increasingly annoyed and frustrated at being constantly ripped out of the game narrative. Constantly looking down at my hands to make sure I was pressing the right buttons made me feel disconnected from the game. I continued making the same mistakes after continuing to play TOTK after this launch stream, and I still make the same mistakes currently. Having the ability to remap the button controls would have made me feel more in control and comfortable playing in a way that felt right to me (Brown & Anderson, 2020).

Because customizability is a recurring theme in game accessibility research (Bozgeyikli, 2018; Mazurek et al., 2015; Pavlov, 2014; Rebecca, 2020), the ability to adjust the key bindings as seen in games like Genshin Impact or The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim would be more conducive to inclusive gameplay. Difficulty adjustments are another common accessibility feature present in games such as Resident Evil 4 and Marvel: Guardians of the Galaxy. While these options are not present in TOTK, other considerations like enemy-type toggles or weapon availability toggles akin to Super Smash Bros could be a viable solution. Other recommendations may include a returnable tutorial stage so players can have the option to re-learn or increase their comfort with the game controls in a safe environment free of difficult enemies (Rebecca, 2020). Employing these features may increase the basic psychological needs of autonomy, relatedness, and competence in line with Self-Determination Theory, a popular framework for games research (Speil & Gerling, 2020).

Visual Data

Visual data in the context of this study involves difficulties with interpreting visual, or on-screen, video game elements. Results concluded that factors affecting visual data processing in a video game context include reading comprehension, spatial awareness, and sensory overload. Unsurprisingly, these findings echo the conclusions of other game accessibility research (Brown & Anderson, 2020; Valencia et al., 2021). I especially found this to be the case with spatial awareness puzzles.

Although there is little research suggesting any correlation between limited spatial awareness and ASD, I could not complete any of the twelve spatial awareness puzzles on the livestream regardless of difficulty without assistance. When attempting to figure out what should be a seemingly simple log puzzle shortly after the tutorial, I loudly sighed and rubbed my face, “This is taking up all of my brain power.” Additionally, there are seven separate instances (Table 1) where I verbally announce my difficulties with spatial understanding. Even with visual cues such as strategically designed divots, I had trouble figuring out the correct placement of the log to complete the puzzle. The game was trying to tell the player, “See this divot right here? This is different. Put that log over here!” but my brain could not see the answer at that moment despite the cues being in plain sight.

In addition to spatial awareness difficulties, I also had trouble with reading comprehension and sensory overload. A video example below details my difficulties with both.

In this video example, I was confused by the mechanic that’s just been introduced. Rather than attempting to comprehend and process the textual information, I just wanted to go away and find something else to do. The information overload from the new environment was too much to handle, and I wanted to leave the dark mine and return to familiar, outdoor terrain. However, my partner suggested that I stay and try to understand the new mechanics. At this point I felt slightly embarrassed; taking the time to read and comprehend the mechanics will only serve to further highlight my incompetencies. So, in order to preserve some type of autonomy and competence (Ryan & Deci, 2000), I decide it’s best if I simply move on. “I’m sure I’ll figure that out later,” I thought.

To address this issue, scholars suggest employing animated instructions over verbal ones, simplifying in-game dialogue, and customizable font sizes and types for subtitles (serif vs sans serif) and sizes (Brown & Anderson, 2020; Costello & Donavan, 2019; Pavlov, 2014). Adding to these recommendations, puzzle-type variations for different learning styles would be appropriate to give players with different learning styles a chance to feel a sense of accomplishment and inclusion.

While problems surrounding Cognitive Impairments may have been an expected outcome of the research, seeing the emotional toll over time as a result of constantly feeling incompetent underscores the need for inclusive game design. However, an unexpected finding was the emergent need for Narrative Regulation.

Narrative Regulation

Narrative Regulation deals with how the player controls the overall flow of the game. Essentially, how does player autonomy coincide with developer intent? Data suggest safety and context cues are the main drivers of Narrative Regulation.

Safety

Safety concerns how the player feels when in-game. A common sentiment on the stream was that I felt like the world was out to get me. This suggests that being able to roam freely and enjoy the world map without much, if any, interruptions is vital in accessible gaming. Having the option to explore at my own pace outside of towns and cities without the threat of enemies attacking would have made me feel more comfortable and at ease during the stream. One of the reasons I enjoyed The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild was because it seemed to have fewer roaming enemies than TOTK and allowed me more breathing room to explore as I pleased. The video example below highlights my negative reaction to a new enemy encounter as I was exploring the map.

In this example, I am frustrated at the combat interruption. I was focused on heading to a new quest marker when, out of nowhere, a tree attacked. Even though it may sound (and look) comical, this enemy encounter was unexpected and ripped me out of the experience. This irritated me as I was intently focused on moving toward an unrelated objective, and did not feel equipped or ready to learn how to fight a new enemy not yet seen in the Legend of Zelda franchise. At one point much later in the stream when a similar encounter occurs I say, “I don’t like to be bothered, I’d rather not (fight). It’s more of a nuisance to me to kill them. If they’re easy enough to avoid, then I will avoid them.” The possibility of being unexpectedly bombarded by enemies made me less excited to explore the map at my own pace.

This need for low-stakes exploration and limited interruptions is notable as it differs from the main discourse of video game accessibility. Most research has focused on UI design and fails to address the game narrative as a whole (e.g. Brown & Anderson, 2021; Cairns et al., 2019; Pavlov 2014; Valencia et al., 2021). I found that being able to freely explore and enjoy the game landscape significantly increased the feeling of “presence” (Slater, 2009) and enjoyment. Relaxation is a significant factor for players (Mazurek et al., 2015), and having designated low or no combat exploration areas outside of in-game cities or towns may increase feelings of immersion and safety.

In addition, safety highlights a common difficulty among individuals with ASD: difficulty in switching from one task to another (Sterling & Jordan, 2007). This difficulty may be due to an increased need for predictability and routine (Flannery & Horner, 1994). Interruptions in video games require the player to switch tasks almost immediately and usually entails engaging in unwanted combat. Being ripped out of a task and forced to focus on another element, or enemy, in the game made me feel like I had no control over the narrative. The ability to toggle enemies that frequently interrupt gameplay like Evermeans (walking trees), Octoroks (rock-shooting octopi), Chuchus (bug-eyed water blobs), and horse-mounted Bokoblins (pig-like humanoid creatures) may also serve to increase feelings of safety and narrative control for players with ASD.

Context

Lastly, context factors in narrative regulation. I noticed that the way I interpret on-screen information is likely different from the developer's intent. For example, I kept pointing out my issues with seeing in TOTK. Not because I was having trouble with my eyesight, but because I could not see what the game wanted me to see. Key elements did not stand out enough to be differentiated from the foreground. The visual cues alone were not enough of a signal for me to see or travel in the way the game, or developers, intended. The video below is an example of this issue.

Even though the design of the shrine differed from the environment, it still did not stand out enough to be seen from afar. This low-contrast issue may be due to being less attuned to visual signals (Costello & Donovan, 2019).

The same difficulties can be applied to directional understanding. With this aspect, what stood out was my tendency to barrel in a straight line toward a quest marker rather than surveying the map and looking for clear, paved roads that would eventually lead to the marker. Any visual indicators signaling me to go one way or another did not work as intended. Lack of directional understanding, as well as issues with low contrast, may also be due to atypical eye-tracking in individuals with ASD. A study by Wang and colleagues (2015) noted that autistic people tend to have atypical eye-focusing patterns, meaning that they may not look at intended focal points in the same way as their neurotypical peers. To combat this, Costello and Donovan (2019) suggest implementing both audio and visual cues in game design. An example linking audio and visual context clues can be seen in God of War Ragnarok with the option to toggle directional indicators. With directional indicators, if a sound or a character is heard in the distance, players will see a visual indicator (arrow) pointing to where the sound is coming from. Even though TOTK has an audio option to toggle proximity to new shrines, it may be wise to implement a similar, optional design with quest markers.

Conclusion

The goal of this paper is to examine the ASD-related cognitive challenges I faced during a weekend-long release stream of the new video game Tears of the Kingdom. In exploring the subsequent negative emotions that followed as a result of lack of accessibility factors, this autoethnography uncovered an emergent need for narrative regulation. By granting players with ASD the ability to control the overall flow of the game in regards to safety and limited interruptions, players gain autonomy over the game narrative and are therefore able to enjoy the play experience as much as their neurotypical peers.

Overall, these findings underscore the need for personalization in video games. The key takeaway of the study is that video games must allow individuals with different cognitive abilities the power to play the game in a way that grants them competency and autonomy. This may involve implementing factors like adjustable difficulty, multiple puzzle-type variations, designated low-combat exploration zones separate from towns and cities, and enemy-type toggles. In implementing more accessibility measures, video games not only become playable for disabled populations - they allow everyone to enjoy the game at their own pace and in their own way.

Limitations and Future Research

As with all studies, this research comes with a set of limitations. The most apparent limitation of this study is the fact that the gameplay was captured on an open, public stream on Twitch. These conditions (large green screen, chat monitoring, public gameplay, video lights, microphones) do not mimic the typical gameplay environment. The increased baseline of overall stimulation over time may have escalated the severity of the results. However, my moderate familiarity with video production, performance, and public streaming serves to somewhat quell these concerns. Future studies may benefit from mimicking a typical, comfortable gameplay environment with minimal external distractions and stimuli. Other studies examining similar accessibility needs may also want to include participants of different levels of video game competency. As a casual gamer who enjoys playing video games as a regular hobby, my comfort with navigating video games is between a novice and an expert. Examining different player levels (non-gamers vs. seasoned & frequent gamers) may provide a more holistic picture of the autistic experience. My study and capabilities may serve as a litmus test of the autistic experience of the moderate gamer.

In addition, one concern of future studies examining gaming accessibility is funding and execution. Heron (2022) notes that implementing accessibility factors does not have to be a costly or burdensome task. Many accessibility issues arise not because the games themselves are inherently impossible for individuals with impairments, but because of the omission of standard features that could make them accessible (p. 30). He argues that significant progress can be achieved by adopting existing good practices that are already present in mainstream game development. This sentiment echoes Spiel and Gerling’s (2021) goal of catering to diverse needs without framing neurodivergence as a deficit.

To wrap up, as the rates of ASD continue to rise (CDC, 2023), it is essential to address the unique challenges faced by this population. As someone who shares these experiences and challenges, I hope this research can spark further research and innovation in the field of video game accessibility for autistic populations, ensuring that everyone, regardless of their neurodiversity, can fully enjoy the world of gaming.

References

Adams, T. E., Ellis, C. & Jones, S. H. (2017). Autoethnography. In J. Matthes (ed.), The international encyclopedia of communication research methods (pp. 1-11). John Wiley & Sons.

Beker, S., Foxe, J. J., Molholm, S. (2018). Ripe for solution: Delayed development of multisensory processing in autism and its remediation. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 84, 182-192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.11.008

Brown, M., & Anderson, S. L. (2021). Designing for disability: Evaluating the state of accessibility design in video games. Games and Culture, 16(6), 702-718. https://doi-org./10.1177/1555412020971500/

Bozgeyikli, L., Bozgeyikli, E., Katkoori, S., Raij, A., & Alqasemi, R. (2018). Effects of virtual reality properties on user experience of individuals with autism. ACM Transactions on Accessible Computing, 11(4), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1145/3267340

Cairns, P., Power, C., Barlet, M., Haynes, G. & Kaufman, C. (2019). Future design of accessibility in games: A design vocabulary. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 131, 64-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2019.06.010

Cairns, P., Power, C., Barlet, M., Haynes, G., Kaufman, C., & Beeston, J. (2021). Enabled players: The value of accessible digital games. Games and Culture, 16(2), 262-282. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412019893877

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, December 9). What is autism spectrum disorder? https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/facts.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2023, March 23). Autism Prevalence Higher, According to Data from 11 ADDM Communities. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2023/p0323-autism.html

Cook, J., Hull, L., Crane, L., Mandy, W. (2021) Camouflaging in autism: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 89, 1-16. https://doi-org.libweb.lib.utsa.edu/10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102080

Corbin, J., Strauss, A. (2012). Strategies for qualitative data analysis. In Basics of Qualitative Research (3rd ed.): Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory (pp. 65-86). SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452230153

Diemer, M. C., Gerstein, E. D. & Regester, A. (2022). Autism presentation in female and Black populations: Examining the roles of identity, theory, and systemic inequalities. Autism, 26(8), 1931-1946. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613221113501

Ellis, B., Ford-Williams, G., Graham, L., Hamilton, I., Lee, E., Manion, J. & Westin, T. (2020). Game Accessibility Guidelines. http://gameaccessibilityguidelines.com/ (Accessed November 15, 2023).

Ellis, C., Adams, T .E., & Bochner, A. P. (2010). Autoethnography: An overview. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 12(1). http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1101108

Flannery, B. K. & Horner, R. H. (1994). The relationship between predictability and problem behavior for students with severe disabilities. Journal of Behavioral Education 4, 157–176. https://doi-org./10.1007/BF01544110

Haigh, S. M., Walsh, J. A., Mazefsky, C. A., Minshew, N. J., & Eack, S. M. (2018). Processing speed is impaired in adults with autism spectrum disorder, and relates to social communication abilities. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(8), 2653–2662. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3515-z

Jones, S. H. (2016). Living bodies of thought: The “Critical” in critical autoethnography. Qualitative Inquiry, 22(4), 228-237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800415622509

IGN. (2023). The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time https://www.ign.com/games/the-legend-of-zelda-ocarina-of-time

Kourtesis P., Kouklari E. C., Roussos P., Mantas V., Papanikolaou K., Skaloumbakas C., & Pehlivanidis A. (2023). Virtual reality training of social skills in adults with autism spectrum disorder: An examination of acceptability, usability, user experience, social skills, and executive functions. Behavioral Science, 13(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13040336.

Malinverni, L., Mora-Guiard, J., Padillo, V., Valero, L., Hervás, A., & Pares, N. (2017). An inclusive design approach for developing video games for children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Computers in Human Behavior, 71, 535–549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.01.018

Mazurek, M. O., Engelhardt, C. R., & Clark, K. E. (2015). Video games from the perspective of adults with autism spectrum disorder. Computers in Human Behavior, 51, 122-130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.04.062

Memzir, E. A. (2020). Qualitative data analysis: An overview of data reduction, data display and interpretation. Research on Humanities and Social Sciences, 10(21), 15-27.

Pavlov, N. (2014). User interface for people with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Software Engineering and Applications, 7(2), 128–134. https://doi.org/10.4236/jsea.2014.72014

Rebecca, S. [Stacey Rebecca]. (2020, October 3). Cognitive Accessibility in Gaming 101 [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SCFcj5yQomM

Roberts, D. (2022) What Are the 3 Levels of Autism? PsychCentral. Retrieved November 24, 2023, from https://psychcentral.com/autism/levels-of-autism

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Salvador-Ullauri, L., Acosta-Vargas, P., & Luján-Mora, S. (2020). Accessibility evaluation of video games for users with cognitive disabilities. In T. Ahram, W. Karwowski, A. Vergnano, F. Leali, & R. Taiar (Eds.), Intelligent Human Systems Integration 2020. IHSI 2020. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, vol 1131 (pp. 793-800). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-39512-4_130

Slater M. (2009). Place illusion and plausibility can lead to realistic behaviour in immersive virtual environments. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B, 364(1535), 3549–3557. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2009.0138

Sohn, E. (2019, March 13). Righting the gender imbalance in autism studies. Spectrum. https://www.spectrumnews.org/features/deep-dive/righting-gender-imbalance-autism-studies/

Spiel, K., & Gerling, K. (2021). The purpose of play: How HCI games research fails neurodivergent populations. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 28(2), 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1145/3432245

Sterling, H. & Jordan, S. S. (2007) Intervention addressing transition difficulties for individuals with autism. Psychology in the Schools, 44(7), 681-690. https://doi-org..edu/10.1002/pits.20257

Srinivasan, H. (2023, July 31). Who Autism Research Leaves Out. Time. https://time.com/6299599/autism-research-limited-essay/

Wall, S. (2006). An autoethnography on learning about autoethnography. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(2), 1-12.

World Wide Web Consortium: Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1 (2018). https://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG21/

Valencia, K., Rusu, C., & Botella, F. (2021). User experience factors for people with autism spectrum disorder. Applied Sciences, 11(21), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.3390/app112110469

Van Assche, J., van der Kaap-Deeder, J. Audenaert, E., De Schryver, M. & Vansteenkiste, M., (December 2018). "Are the benefits of autonomy satisfaction and the costs of autonomy frustration dependent on individuals' autonomy strength?". Journal of Personality, 86(6): 1017–1036. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12372

Wall, S. (2006) An autoethnography on learning about autoethnography. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(2), 1-12.

Wang, S., Jiang, M., Duchesne X. M., Laugeson, E. A., Kennedy, D. P., Adolphs, R., & Zhao, Q. (2015), Neuron, 88(3), 604–616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.042